Don’t Do The Wrong Things Right

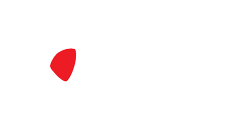

If you’ve been around the digital marketing block for a while, you’ve probably encountered some variation of linear ‘funnel optimization.’

The underlying idea is that if you make each part of your business better, your overall results will improve.

- More clicks on your ads = better business.

- More leads = better business.

- More sales = better business.

But here’s the problem: that’s not how the world actually works. What seems intuitive, smart even, is often counter-productive.

Linear optimization assumes — incorrectly — that every click, every lead, and every customer is qualitatively the same.

Of course, that’s not true. Not even close.

You can get more clicks, more leads, and yes — even more customers — and your business might (and likely will) perform worse overall!

Management consultant, author, and educator Peter Drucker observed an enormous distinction between doing things right and doing the right things.

Systems theorist, author, and Wharton School professor Dr. Russell Ackoff took Drucker’s idea to its logical conclusion, saying, “the righter you do the wrong things, the wronger you become.”

What should we do instead?

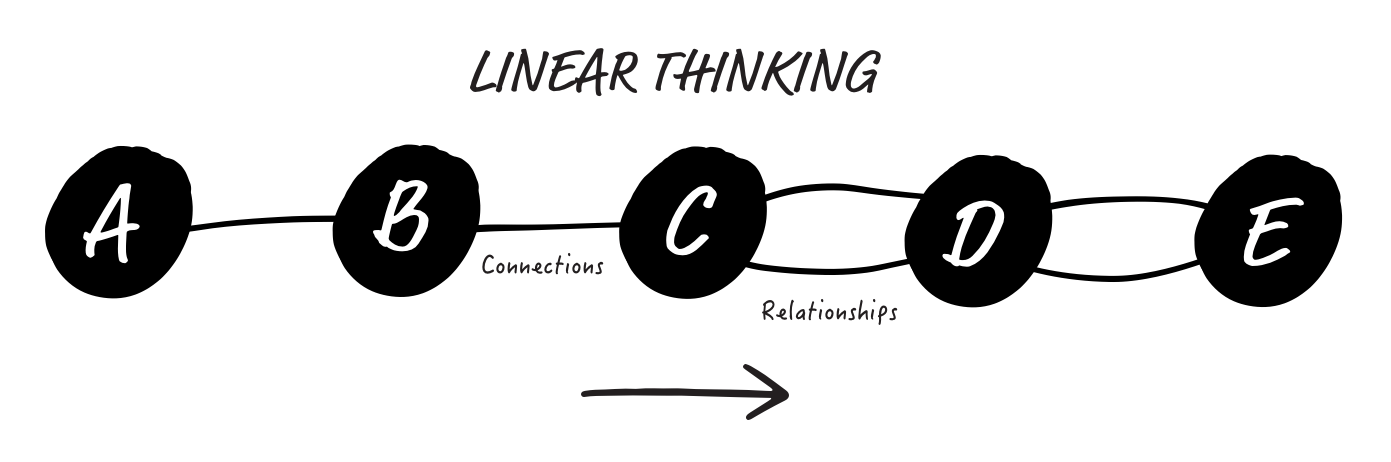

Systems theory shows us that it’s the way the parts of a system interact — not how they act independently — that actually improves performance.

But what does that mean?

We’re glad you asked…

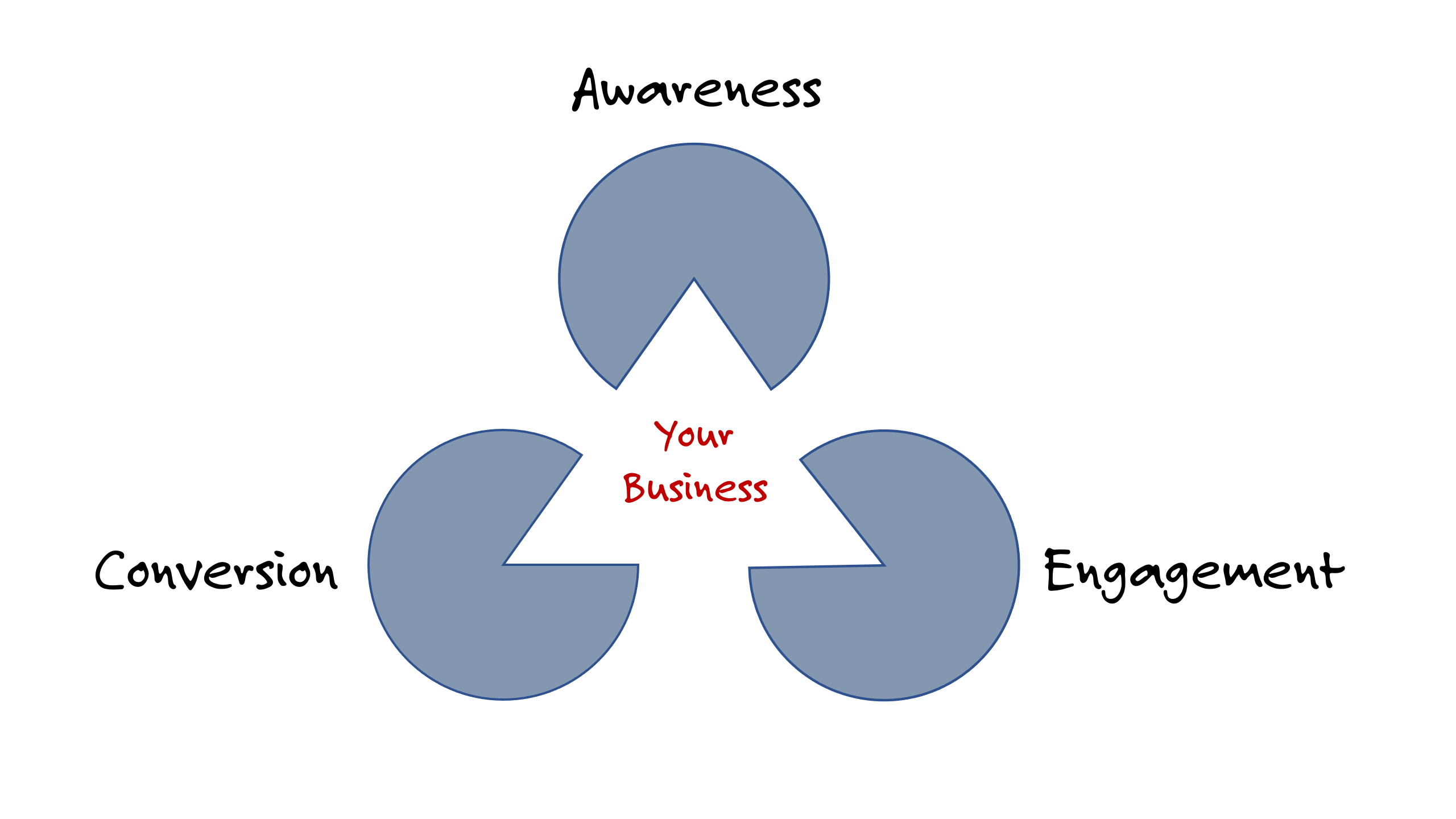

Let’s start with the three essential components of a business system:

- Awareness

- Engagement

- Conversion

Broadly speaking, awareness is how your audience knows you, your business, or a specific offer you have created (or are promoting) exists.

Engagement occurs when someone in your audience takes a step closer to you, interacts with you in a meaningful way. (For example: by clicking on an ad, opting in to receive your emails, attending a webinar, etc.)

And conversion occurs when someone buys something.

Individually, awareness, engagement, and conversion are necessary, but none of them on their own is sufficient. All three must be present before a business exists.

This is where systems theory can become very confusing (and counterintuitive).

Fortunately, a visual can help.

This image is called a Kanizsa Illusion, and it’s a useful representation to better understand systems theory:

Each of the ‘Pac Man’ shapes in the corners represents your methods for creating awareness, engagement, and conversion. The white triangle representing your business is an emergent property of how those shapes interact.

Read that again; it’s important.

This is the central insight of systems theory. What we think of as our business isn’t a separate thing independent of how we create awareness, engagement, and conversion. Instead, our businesses emerge from the way those parts of our systems interact.

If we take away any of the ‘Pac Man’ shapes in the corners, the triangle disappears. And, if we take away awareness, engagement, or conversion, our businesses will disappear too.

The Kanizsa Illusion represents another tenet of systems theory described by Dr. Ackoff.

“It’s the way the parts fit together that determine the performance of the system, not how they perform taken separately.”

(And, in this vein, each part can’t be “optimized” separately without it affecting the entire system, and consequently, the emergent behavior of the business.)

The best way to understand this idea is with examples. Unfortunately, they’re representative of real situations we’ve seen happen far too many times.

Business X creates ads, landing pages, emails, and an offer that work together to produce happy customers. Everything is congruent, humming along, and the business, as a whole, is working.

But then, with the best of intentions, someone decides to make a part of the system “better.”

“Agency X looked at our Facebook ads and they think we’re paying WAY too much for leads … their ‘magic method’ will lower our lead costs by 20%. I already signed the contract!”

…or…

“Our landing page opt-in rate is too low. I think we should give away more free videos with our lead magnet…”

…or…

“We need more urgency after the offer is revealed. Let’s add a countdown timer and a fast-action bonus to the sales page…”

You can probably guess what happens…

Parts of the system perform ‘better’ — less expensive leads, higher opt-in rates, and more customers (before refunds) — but performance for the business, as a whole, suffers.

Those cheaper leads don’t convert as well.

The free videos are saved on the desktop for “later” (which never comes because there’s always something new, bright, and shiny to download).

High-pressure sales converts more customers in the short term, but refund rates increase, and customer satisfaction falls off a cliff.

The righter you do the wrong thing, the wronger you become.

Fortunately, there is a (much) better way.

First, we need a clear, precise definition of success for our business as a whole.

For example, our business is successful when it produces happy customers. (Feel free to steal our definition — we don’t mind.)

Note: “Happy” is a meaningful distinction. There’s a world of difference between generating a customer (through any means possible to maximize sales), and a very specific customer who feels an emotional pull to want to interact with us more intimately (through our courses, emails, workshops, and free trainings). Happy customers don’t want refunds and are also more inclined to purchase more (and more) over time.

In system terms, the rate at which your business system produces results is called throughput. When we create more happy customers, our throughput increases. Simple, elegant, effective.

Second, evaluate every ‘improvement’ you’re considering with a simple question:

Is this likely to increase throughput for my business?

Or, a variation of that same question (which you can ask others as well — especially anyone with ‘magic methods’):

HOW — specifically — will this intervention improve throughput for my business?

Remember that every (every!) change — big and small — will produce emergent results elsewhere in the system and often in multiple places.

These questions often reveal where we’re making leaps of faith and can point the way to better (and often counter-intuitive) opportunities.

For example, “how will cheaper leads create more happy customers?” (This question will immediately uncover a LOT of flawed assumptions.)

“How will more leads bribed with additional free content create more happy customers?”

And, of course, “how will coercing people to buy faster rather than letting them buy when they’re ready, create more happy customers?” (Hint: it won’t.)